October 13, 2025

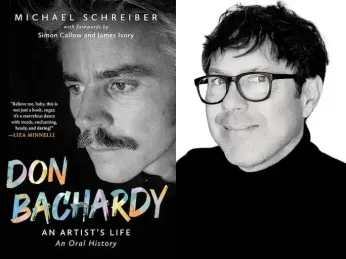

‘Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life’ – Michael Schreiber’s oral history shares plenty

Jim Provenzano READ TIME: 2 MIN.

If you’ve ever had a lengthy conversation at a dinner party with an accomplished artist, you know how woven they can be in their stories, but also how some discuss their accomplishments as if it were outside themselves, that their talent was a gift, not the results of years of practice and work.

Such is the case with “Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life,” Michael Schreiber’s oral history, which at length delves into the experiences of the prolific painter and decades-long partner of acclaimed author and screenwriter Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986).

The richness of his celebrity contacts is evident in the book’s advanced praise from no less than Liza Minnelli, actors Michael York, Joe Gray, Ian McKellen and the late author, Edmund White. The book also has two forwards from actor Simon Callow and filmmaker James Ivory.

Bachardy pretty much tells everything about his life, starting as a young boy in Santa Monica, and how he and his older brother Ted became devoted fans of movie stars and cinema. Their mother often took them to the movies while their father worked overtime in the aerospace industry in the 1950s.

Ted and Don became more drawn to Hollywood culture by at first sitting in the grandstands at movie premieres, but soon crashed the gates dressed in dapper suits, where they requested autographs and had themselves photographed with luminaries of all kinds, including Marilyn Monroe.

His older brother Ted brought his younger brother Don to certain parties where older gay men were present. It was a while before Don realized that, like him, his brother was also gay.

Don & Chris

Bachardy first met Christopher Isherwood at the Santa Monica beach, and even though his brother got to sleep with him first, they ended up hanging out together and then dating, with Don more often staying at one of Isherwood’s residences.

Despite a 30-years age difference, the two formed a bond that gradually developed after repeated meetings. Isherwood later introduced Bachardy to some of Hollywood elite, as he had written a few screenplays, and had an ‘in’ with the movie stars. Most knew they were gay and partners.

And most were polite, but some were slightly homophobic, or loudly so. Bachardy shares a story about Joseph Cotton, who, drunk at a party, berated the young Bachardy to his face as “half-man,” but out of earshot of Isherwood, who could’ve had some influence on his career.

Woven through Bachardy’s memories are the encouraging words from Isherwood for Bachardy to develop his artistic talents. He took lessons in Los Angeles, New York and even London, where time away from Isherwood was difficult. But while Bachardy was devoted to his elder partner, he needed to have his own adventures and experiences, including sexual ones.

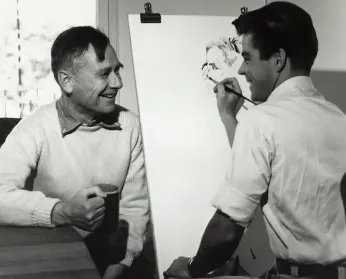

Primarily, Schreiber asks about Bachardy’s experiences with celebrities and his talent for portraiture. Having drawn or made paintings of actors and actresses for decades, his work is in the thousands.

He frequently talks about how he tries to capture the real essence of people, often in serious poses, never the varnished prettified version of their looks.

While many of the famous people turned out to be extremely polite and welcoming, like Bette Davis (her wry compliment after seeing one of her portraits; “There’s the old bag!”), others were a bit persnickety about what they perceived as flaws depicted in their portraits like Joan Crawford, who donned a huge wig, or Joan Fontaine, who winced at imperfections while her embattled sister Olivia de Havilland sat patiently for hours for her portraits.

Although he later developed a talent for colorful nude male paintings, Bachardy had an early preference for painting women’s portraits, and usually got to their likeness much more easily.

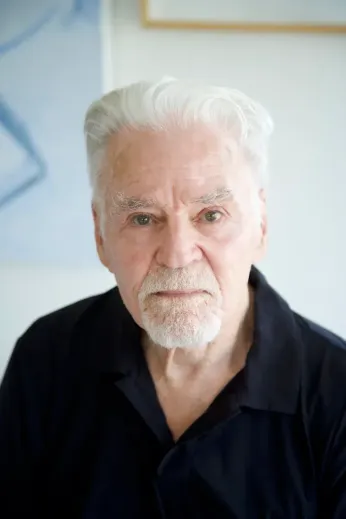

Bachardy’s multiple drawings of Isherwood, who encouraged such work even in his last living months, offer a stark dramatic contrast to the more vibrant paintings. Bachardy, now 91, even talks about his impressions of the 2024 Broadway revivals of “Cabaret,” based on Isherwood’s “Goodbye to Berlin” and other works. Bachardy says that Isherwood didn’t like the original film and never saw a theatrical production.

Schreiber, whose previous books include “The Young and Evil: Queer Modernism in New York, 1930–1955” and “This American House: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Meier House and the American System-Built Homes,” asks probing questions that include references to many of the actors and actresses that the reader may not be familiar with.

There is a bit of repetition throughout, but as with any lengthy conversation, stories get re-woven in remembrance.

Several of Bachardy’s artworks are shown in the book. Suggested additional reading includes Bachardy’s own books of artwork and portraits, and some of Isherwood’s novels (particularly “A Single Man,” the title of which was Bachardy’s suggestion) and stories, as well as the films for which he wrote or co-wrote the screenplays.

Also, a viewing of the documentary “Don and Chris: a Love Story” would be a good follow-up or advance viewing. It’s free and available on Tubi.com.

‘Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life,’ an oral history by Michael Schreiber, $29 hardcover, $14.54 Kindle, $15 audiobook, $46 audio CD; release date October 28. Citadel Press/Kensington Publishing Corp.

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com